Betsey Wynne

Betsey Wynne 1778 – 1857

By Ken Harris

Betsey Wynne was the second of five sisters, born 19th April 1778 to Richard Wynne and his French wife Camille de Royer. Richard Wynne, who was born in Venice, and lived much of his early life on the continent, had inherited a large estate at Falkingham (now Folkingham) in Lincolnshire, which he sold after the birth of his fifth daughter in 1786, and then left Britain with his family to travel around the continent. On 17th August 1789, Betsey and her younger sister Eugenia, both started writing diaries, and Betsey continued writing a daily record of her life, with very few breaks, right up till her death in 1857.

The family travels were heavily influenced by events in France, with the French Revolution in 1789, followed by the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte and the lengthy wars between Britain,

France and other continental countries which ensued. In 1796, as Napoleon’s army advanced into Italy, the Wynne family were evacuated from Leghorn by Captain Thomas Fremantle in his Royal Navy ship the Inconstant.

Betsey – by now an accomplished 18 year old – was swept off her feet by the ‘good-natured, kind and amicable, gay and lively’ Captain, and whilst the 30-year old Captain Fremantle had a lot of other things to occupy his attention, he soon fell in love with the young Betsey.

The course of true love did not run smoothly at first, particularly as Fremantle was from a relatively modest Protestant background, whilst Betsey was a member of a wealthy Catholic Family. But eventually the match was made, and Richard Wynne settled 8,000 pounds on the young couple. The wedding took place in Naples on 13th January 1797, in the home of Lord William and Lady Emma Hamilton (the Emma Hamilton who was later to become Admiral Nelson’s lover).

Betsey was given away by Prince Augustus (sixth son of George III). She then left her family, to live with her husband on the Inconstant.

Thomas Fremantle was a close friend and colleague of Horatio Nelson, and they found themselves engaged in a number of joint actions in the Mediterranean. However, in July 1797, during an expedition to try and take the town of Santa Cruz on the island of Tenerife, both men were injured in their right arms. Nelson had his amputated, whilst Fremantle’s was saved but it caused him a lot of pain for years afterwards.

Nelson wrote what is thought to be his very first note with his left hand to Betsey ‘God bless you and Fremantle’. Fremantle and Nelson together with Betsey Wynne sailed back to England to recuperate. Nelson made a quick recovery, and was back in action in 1798, when he came to particular prominence in the destruction of Bonaparte’s fleet in the Battle of the Nile, thus scuppering Bonaparte’s plans to move into India.

Meanwhile Thomas Fremantle and his wife Betsey and a new-born baby son, also named Thomas, moved into ‘The Old House’ in Swanbourne which they purchased for 900 guineas. So began over 200 years of the Fremantle family’s association with the village. As Betsey’s parents both died soon afterwards, her younger sisters also came to live with her.

The image of Betsey Wynne (based on a 19th century painting) is used at the Betsey Wynne Pub and Restaurant, Swanbourne, which opened in 2006. The pub is owned by the Fremantle family.

Two more children – Emma and Charles – were born to the young couple before Thomas Fremantle was well enough to return to sea, captaining the Ganges and taking part, alongside Nelson, in the action at Copenhagen (when Nelson famously turned a blind eye). The family spent much of their time socialising with the Duke of Buckingham at Stowe or in London, but whilst in Swanbourne, Betsey took a great interest in her new estate, and managed its affairs in her husband’s absence, as well as overseeing an increasingly large family of children. Thomas Fremantle spent further time back in Swanbourne, before again being called up in 1805 to Captain the Neptune.

He joined his old friend, by now Admiral Nelson, in patrolling the Atlantic coast of Spain, and took a major part in the ensuing Battle of Trafalgar, where Nelson was killed. When news of this historic sea battle first reached Swanbourne, Betsey was alarmed by the reports, but swiftly got news of her husband was safe – though she was saddened to hear that Horatio Nelson was dead.

It was to be over a year before Fremantle was able to return from active duty in the Mediterranean, and meet up with his family again. During this time, the Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger had died and a new administration, led by William Grenville, the brother of the Duke of Buckingham, was appointed as Prime Minister and Fremantle had high hopes of an appointment to the Admiralty. However, politics worked against him for a while, as the King wanted his favourites put into positions of power, but when he finally did return to England, Fremantle was made a Lord of the Admiralty and the safe Parliamentary seat of Sandwich was made available to him. Betsey and Thomas moved down to London anticipating a lengthy stay in this new life. However, Fremantle’s position in Parliament was very short lived – just five months – although during this time, the Act to Abolish the Slave Trade was passed. In March 1807, the government fell over its attempt to pass a bill on Catholic Emancipation – which the King opposed. Fremantle lost his hope of further political advancement, and he and Betsey returned to Swanbourne.

Thomas was then offered various positions, most of which took him away from home for spells at sea. Despite this, Betsey gave birth to nine children in total, her final child, Stephen, being born in August 1810. All but one of these children lived into adulthood.

In June 1815, Fremantle was offered a post as Flag Officer in the Channel Islands and Betsey joined him there. For the next four years, she stayed with her husband, who was made Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean in January 1819, and was promoted to Vice-Admiral in the August of that year. However, on 19 December 1819, quite unexpectedly, he was taken ill and died whilst in Naples. Betsey’s world was turned upside down.

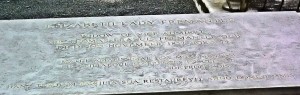

The grave of Lady Elizabeth Fremantle in Cimiez, Nice. Reproduced by kind permission of Gravestonephotos.com

Her diaries for the period up to her husband’s death have been published as The Wynne Diaries, although she lived for another 37 years, dividing her time between Swanbourne, London and visits to the continent. She continued to keep her diaries throughout this later period, and her activities after her husband’s death are still being researched. She eventually died at Cimiez near Nice on 2 November 1857, aged 79, and is buried there.

RETURN to Interesting People Category

This post has 3 Simple Fields-fields attached. Show fields.