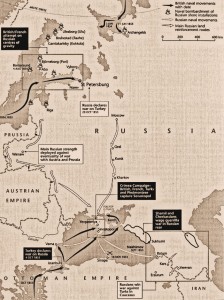

Crimean (Russian) War

Swanbourne and the Crimean War

By Ken Harris

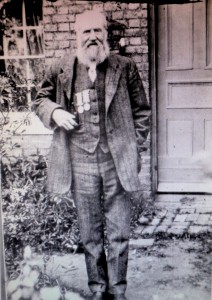

John Roads

John Roads, or Rhodes (both spellings seem to have been used) was born in East Claydon in or around 1832. In the picture shown (left), his Crimean war medal has four bars which are said to have been for Inkerman, Balaclava, Alma and Sebastapol, so he was almost certainly present at all of these battles. In the 1901 census, he was living in Swanbourne, and is described as a Retired Army Pensioner. He had a son, and this son had two daughters who were named Alma and Balaclava (another indication that he fought at these two battles).

John Gurnett

John Gurnett was born in Swanbourne on 23rd May 1815, the son of Benjamin and Sarah Gurnett and was christened in the Church on 20th July 1815. In 1834, he enlisted in the Royal Marines at Aylesbury when aged 19, for a bounty. He served on HMS Asia between 1836-1841, but from 1841-1844 he served on HMS Cornwallis, and in 1845 he served on HMS Superb. The 1851 census has him living in Woolwich, as a private on guard duty at the Royal Dock. He married Ann Maria Davis in Woolwich on 19th July, 1856. He is listed in the 1871 census records as an army pensioner and he died in 1880, aged 64.

William Gurnett

William Gurnett was 10 years younger than John, being born on 10th June 1825, also in Swanbourne. However, unlike his brother, he was not christened since in 1819, his parents had joined Swanbourne Baptist Church. In the 1841 census, he was described as an agricultural labourer living with his parents in Swanbourne, but in 1844, he enlisted in Aylesbury and served in the 4th Company of the Royal Marines based at Woolwich. His whereabouts in 1851 is unknown, but he was in Crimea for the Crimean war where he fought at the Battle of Inkerman (as did John if family tradition is to be believed). According to one Crimea War expert, the Royal Marines were used as guards at the port at Balaclava and Inkerman was the only battle at which they fought.

William married Charlotte Alderman on 2nd March 1862 at Woolwich Parish Church, Kent, in the presence of John Gurnett [almost certainly William’s brother] and Rebecca Alderman [probably Charlotte’s sister]. William was described as a Private Royal Mariner. Charlotte Alderman was also from Swanbourne, being born here on 16th January 1839. She was living at 12 Samuel Street, Woolwich, at the time of the marriage, whilst William was in the Marine Barracks.

The couple had two children whilst living in Woolwich, a daughter Hannah Rebecca (14th September 1863) and a son John William (13th March 1865). [John is said later to have attended a boarding school for the eldest sons of Royal Mariners but hated it and came back to Swanbourne.]

On 10th June 1865, William was discharged from the Royal Marines after 21 years service, and he and his family moved back to Swanbourne with William on a naval pension in around 1866. They joined Nearton End Primitive Methodist Church in Swanbourne, where they were stalwart members. They had six more children in Swanbourne – Charlotte Ellen (b 6th November 1867); Mary Alice (4th June 1869) Charles Edwin (8th August 1871); Amy Florence (1st April 1873); Edith Minnie (5th February 1877); Alderman Ernest (25th June 1885)

In 1871, the family were living in Nearton End and William was described as a Greenwich out-pensioner (an old sailor attached to Royal Greenwich Hospital). In 1873, he took part in the farm workers’ strike in Swanbourne. In the 1881 census, he was still living in Nearton End, and was described as an agricultural labourer. He died in Swanbourne on 16 December 1887 at the age of 62 years. Charlotte is recorded in the 1901 census as a widow aged 62 living her daughter Edith and son Ernest. She died in Swanbourne on 1st February 1926 aged 87 years.

(We do not have any further details about the actual contribution which these 3 men made to the battles in which they fought, but more research may throw up other interesting facts.)

Charles Fremantle

Charles Fremantle was the second son of Admiral Thomas Fremantle who had fought at the Battle of Trafalgar. He was born in Swanbourne at the Old House on 1st June 1800, and perhaps his greatest claim to fame was to have taken possession of Western Australia for the Crown in April 1829, with the port of Fremantle being named after him. But he had a distinguished career, and following his work during the Crimean War, he was awarded the KCB. He was promoted to Admiral in 1864, and died in London in 1869.

When he arrived in the Crimea in July 1855, the Anglo-French armies were laying siege to Sebastopol, which was the Russian Naval base. The previous winter had been very bitter, and the besiegers were suffering badly. It was a formidable task to supply an army at such a distance from home, especially as all the supplies of the British army had to pass through the small port of Balaclava. When he arrived in Balaclava, he was totally unprepared for what he found. For one thing, he had not realised that the entire responsibility for the naval transport service was to fall on him, and when he did he was outraged. He wrote to his brother Thomas in Swanbourne ‘It is surprising to see the Shells continually flying night and day, but what damage they are causing we cannot tell. ..All the Captains are very tired of being here, nothing to do, and no prospect for them….Everybody is expecting another winter here, and the sooner it is prepared for the better. .. ‘. There was much for him to do to make ready for the year ahead.

In a further letter in August, he wrote “I have now been here long enough to find out that I have been let into a most troublesome and unsatisfactory duty. No one can form an opinion of what this Harbour is who has not seen it and the numberless ships that bring provisions and stores for the supply of the Army is endless, the demands, requisitions from all departments of the Army come in every hour, all expecting to be complied with. I foresee great difficulties in the supply of the Army for the Winter, unless Storehouses are built on shore and filled with a sufficient quantity to feed them we shall be in a great mess, at present the Commissariat supply Fuel, Hay, Barley and other things from day to day, this is well enough in the summer but in the Winter when ships cannot lie off there will be a want of the same things as last Winter. I have represented it, and requested that Storehouses be erected sufficient to hold a supply for 30 days, but whether it will be attended to, I know not, the Departments do not pull together, and on shore there is no arrangement or forethought.

Everybody is dead sick of the whole affair and not one Officer that I have spoken to who would not give much to get away. Our losses are very great, every night in the trenches casualties between 30 and 50, the Russians throw their shells with the greatest precision amongst our poor fellows at work, and there is more fever than is allowed in the Army. ..

Fremantle worked hard to bring order out of chaos. The correspondent of The Times, wrote in one of his despatches “Admiral Fremantle displays the greatest energy and zeal, as well as a perfect capacity for the duties of a post which requires no ordinary application and ability, and he has brought the harbour of Balaklava into as good order as any dock in London or Liverpool.”

By this time 90,000 men and 20,000 horses were being supplied through Balaclava. Grain was brought from the Danubian provinces of Turkey, straw from the Sea of Marmara, mules and donkeys from Beirut and Antioch, Genoa and Barcelona. Following one of the suggestions made by the commissioners, a Land Transport Corps had been set up. “They have 12,000 Animals, with such a set of scoundrels of all nations to manage them I never saw before,” Fremantle told his brother. “More horses and mules are coming in daily and I have sent transport for 150 Camels – this is all absurd as there is no prospect of the Army taking the field ~ and in the winter we shall have a quantity of these beasts eating their tails off.”

Another assault upon Sevastopol was fixed for 8 September, and this time it was successful. In another letter to his brother Tom, he wrote: …”I envied your family party at Swanbourne, it is I know much jollier than even having taken Sebastopol, but thank God! that is accomplished, and I have walked and ridden all over it, but how it became ours is still an Enigma.”

He goes on to give his own account of the attack which was a major set-back for the Russians, although it did not bring the war to an end.

As winter approached, the Admiralty were much concerned that there should be no repetition of the disaster of November 1854 when 48 transports lying outside the harbour at Balaclava were wrecked in a storm. Charles Fremantle was busier than ever, for he not only had to supply the army before Sevastopol and the garrison at Kertch (taken in May 1855), at the entrance to the Sea of Azov, but also to mount various expeditions. One of these was to the fortress of Kinburn, on a spit of land off the mouth of the Dnieper River, of which Lyons wrote to him: ‘I trust we shall make him [the enemy] feel all the discomfort and inconvenience of having a Gibraltar at the Head of the Black Sea.’

The council of war in Paris turned into a peace conference, since the Emperor Alexander (who had succeeded his father in the previous year, at the height of the war) was anxious to bring the war to an end. An armistice was declared on 26 February 1856 and peace was signed on 30 March.

This was the signal to begin the vast operation of evacuating the Crimea. The stores which had begun their journey from England weeks before in preparation for a spring offensive were still arriving in enormous quantities.

“The job of clearing the Crimea of our Army with its Material will be very tedious, and with the Transport we have at our disposal it can not be done under at least four Months, and I should then look to the Line of battle Ships carrying Troops. From a return I lately got from General Windham the number to be embarked was very little short of 80,000 and Animals including Land Transport about 17,000. This does not include the Sardinians and their number is about 15,000 and 3000 Cavalry and Artillery horses. “

Fremantle was expecting the Baltic Fleet to arrive in the Crimea to help with the embarkation. Their Lordships had in fact no intention of using men of war as transports, but they changed their minds when Queen Victoria herself said that she hoped nothing would be spared to bring her gallant army home before the summer with its attendant risk of cholera.

The result was that in the three months after 12 April 1856, 101,435 officers and men, 15,865 horses and 3,850 tons of stores were removed from the Black Sea in British ships. All the men were moved in steamships. In addition quantities of stores and many thousands of draught animals were moved to Constantinople and different points around the Black Sea where it was thought there might be a sale for them.

As the operation drew to a close an odd residue of passengers and baggage was left at Balaclava. It included various camp followers, vast numbers of Tartar refugees (to whom Turkey had offered asylum) – and a camel for the Zoological Society of London.

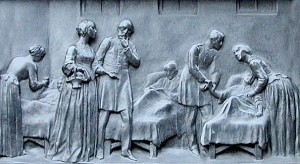

“I find on the departure of the different Regiments a large accumulation of Soldiers Wives, they all claim the protection of Miss Nightingale who has requested me to find passages for them, and as they must go home I have desired the Thames Sick ship to receive them, and about 80 including several Lady Nurses will be embarked in her. I had it quietly hinted to Miss Nightingale that this would be a good opportunity for her to return to England, but she declines till the end, altho I cannot see what object she can now have in remaining as the Hospitals are very nearly empty, and desirable Ships are not found every day, but of course I cannot interfere with her arrangements.”

Ten days later, the determined Miss Nightingale was still there.

“Miss Nightingale still remains, but I hope that she will leave with all her Squadron of Nurses in the next Sick Ship, which I have offered to place at her disposal. I am sorry that she delays her departure, as….it is very desirable that she should go away, but Ladies are difficult to persuade, particularly this one.”

Sir Charles Wood, First Lord of the Admiralty, wrote cordially thanking him for his services and telling him to come home when and how he liked. Charles replied on 12 July : “Having seen the last of the Troops and Stores leave this Port this day, and the place given up to the Russian Authorities I purpose returning to England in the “Banshee” to Marseilles then through France.” He was assured that his work would get recognition through the award of the K.C.B. which he duly received on 29th December 1856.

[Many thanks to Neil Rees (a descendant of the Gurnett family) for the information on John and William Gurnett and John Roads, and to Tom Fremantle for allowing me to borrow a copy of “The Admirals Fremantle 1788 – 1920” by Ann Parry, from which I have gleaned most of the information about Charles Fremantle’s role at the port of Balaclava. If you have any further information about any of these people, or of any other Swanbourne people who were linked with the Crimean War, please get in touch.]

CLICK TO HEAR THE CHARGE OF THE LIGHT BRIGADE poem by Tennyson about the Crimean War