Pitkin Family

Includes evidence given to Royal Commission on Old Age Pensions

Thomas Pitkin and the Old Age Pension

By Ken Harris

On Wednesday 14th February 1894, Thomas Pitkin, a life-long inhabitant of Swanbourne, appeared before the Royal Commission on Old-Age Pensions, being held in the Queen’s Robing Room in the House of Lords, Westminster. He was 67 at the time, and the evidence which he gave about his own personal experiences formed part of the evidence considered by the Commission and which formed a growing body of evidence for the need for some kind of state-funded pension for the elderly. However, it was not until 1909 that a pension was eventually granted, and Thomas himself only benefited for a year or so before he died in 1910.

Thomas Pitkin was born 1826, to a single mother, Sarah, who was described as a servant, and was baptised at the Parish Church on 2nd April – which he says, in his evidence, was his birthday. He appears in the 1841 census as a 15 year old agricultural labourer, living with his mother, step-father and his step-father’s 15 year-old son, as his mother had married Benjamin Gurnett, a widower with a son Thomas’s age in 1833. Whether or not it was a love-match, it must have been a mutually beneficial arrangement. But Sarah died in August 1842, and then on 8th November 1846, Thomas, recorded as a 20 year old labourer, married another Sarah (Hobbs), a Swanbourne Lacemaker, also aged 20.

Together, Thomas and Sarah went on to have 8 children – William, George, Charles (died in 1852 aged 10), Arthur, Henry, Jane, Daniel and Mary Ann. By 1871, they had moved to Mursley, where Thomas and the two older boys worked as farm labourers, whilst Sarah was still lace making and Jane was a straw plaiter. Between themselves, they probably managed to earn enough for a reasonable standard of living. But Sarah died in 1874, aged just 47, and by 1881, Thomas had moved back to Swanbourne, living in Nearton End and continuing to work as an agricultural labourer. At that time, only Henry, a 25 year old agricultural labourer and Mary Ann, a 15 year old Lacemaker, were still living with him.

In 1891, the 65 year old Thomas was living on his own, Mary Ann having married Daniel Elmer from Whitchurch in 1883. However, she was living only a few doors away, and this was still the situation at the time that Thomas appeared before the Royal Commission. But by 1901, Thomas, now aged 74, had moved in with Daniel, Mary Ann and their five children.

NEW – See as a PDF:- Thomas Pitkin Evidence to the Royal Commission

On December 14th 1903, an item appeared in the Bucks Advertiser, as a statement by Thomas Pitkin of Swanbourne:

“I was born in April, 1826, so that I shall be 78 years old next April. I was bred up as a fatherless child, and suffered very much until I was 10 years of age when I began to work. The first year I went to work I had nothing but my dinner for wages; then after that I had 1s 6d. per week. There were plenty of men in those days as big as our Tom (referring to a grown-up young grandson) who went to work for 4s. per week. Oh, yes, they were the ‘good old times’, so called, but they weren’t good times for the labourers. I got married when I was nearly 21, and at that time I was earning 8s. per week; that was in the good (?) old days of Protection. Food and fuel especially were very dear; there was a great coal barn in the village, over against the Church, and a faggot pile; a single person was allowed to go to this barn once or twice a week and buy 1/2 cwt. of coal and a faggot; a married man with a family could have a double quantity if he could find the money. Coal was about 1s. 8d. per cwt. On account of things being so dear and wages so low, petty thieving was very common; the men used to lop the trees during the night, and take the wood home to burn (stag-lopping it was called, as they used to cut the branches off about a foot or eighteen inches from the tree); the men used to walk from here to Whaddon Chase, nearly three miles at night to pick up rotten wood and carry it home to burn; and some have been known to go two or three times in one night. Joe Chamberlain says we shall get higher wages if we have Protection; but we had a great deal lower wages in those times. I well remember the time when Sir Robert Peel fell off his horse and was killed, and one old farmer in this neighbourhood said he ought to have been killed two years before. I also remember quite well the time before the Russian War, when wheat was 15s. per bushel, and when we had to eat barley bread. At that time bread was 11½d for a 4 lb. loaf, and tea 6s. a pound (at 4s. a pound it was very poor stuff). I was then earning about 10s. a week. Ah! those were hard times. I remember a man named Acland coming to Winslow Market Hill and speaking about cheap bread. After the meeting, as some young women were going home and talking about what they had heard, one of them shouted and said ‘I be for a cheap loaf,’ and the other one said’ Acland for me’, and these persons were known for years after by the names of’ Acland’ and ‘Cheap Bread’.”

Thomas died in 1910, aged 84, and was buried on 29th June in the cemetery in Swanbourne. He would have started drawing an old age pension of 5s a week from January 1909, following the passing of the Old-Age Pension Act 1908, by the Liberal Government.

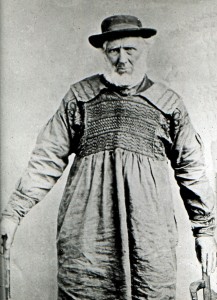

As well as his contribution to the Royal Commission, he is remembered as a district councillor and also one of the last, if not the last, of the Swanbourne labourers to wear a smock. The smock is now part of the collection held in the Aylesbury Museum.

A note of his death appeared in the Bucks Herald of July 2nd 1910:

“I regret to note the death of Mr Thomas Pitkin of Swanbourne at the ripe old age of 84. Although he never rose above the rank of a farm labourer he was in many ways a notable man. He was the first district councillor for his parish, a post which he occupied until advancing infirmities compelled him to relinquish it; also a local preacher among the Primitive Methodists with a gift for simple speaking. He was one of those selected to give evidence before the committee on old age pensions, which sat in 1884, and had the honour of being questioned by the King (then Prince of Wales) and others. He was one of the few remaining men who wore that now almost obsolete garment, the ‘smock frock’.”

As was often the custom at elections in those times Pitkin had a slogan: ‘Don’t vote for Darky whose top of the plan.

Vote for Pitkin the labouring man.’His opponent Cornelius Colgrove was nicknamed ‘Darky’. He was very unpopular with the labouring class, but did eventually succeed Pitkin as District Councillor.

I do not believe that Pitkin could have achieved so much without a degree of patronage from the second Lord Cottesloe.