Agricultural Workers Strike

The Swanbourne Agricultural Workers’ Strike of 1873

By Ken Harris

For 3 weeks in March 1873, around half of the agricultural workers living in Swanbourne went on strike in a bid to raise their weekly wage from 12 shillings per week to 15 shillings. The story of the strike, its causes and its results has been explored by local historians because of the wealth of related information which is held in local archives, and the insight which it gives into the politics and social conditions of the time.

There are several causes which contributed to the strike. There was discontent amongst the workers because of a long-standing grievance over their use of allotments. When the open fields of Swanbourne had been enclosed 110 years previously in 1763, access to the common lands was lost, and in its place, a 9-acre field was allotted to the vicar and churchwardens for the benefit of the poor of the village. This was scant recompense for what had been lost, but a time had come when this field was divided into 80 or so separate allotments which were rented to the workers at 6d per year. However, in 1866, the vicar and churchwardens decided to evict the workers so that the field could be let to a local farmer for a much higher rent. Whilst this would benefit the very poor, the hard-working labourers lost out. Some refused to give up their allotment, which led to a court case against 2 of them. These 2 workers lost and were left with legal costs of over £50 per year – leading them into bankruptcy and possibly imprisonment.

This running sore came to a head again at the beginning of 1873, probably because of the increasing financial pressures on the labourers. Prices of staples, such as bread and coal were rising, whilst wages remained static. Also cottage industries such as straw-plaiting and lace-making, which had previously provided additional sources of income, were in decline. To make matters worse, schooling for those aged 10 and under had become compulsory, denying them the opportunity for gainful employment.

The Lord of the Manor was Sir Thomas Fremantle, who owned most of the lands and houses in the village. Although coming up to his 75th birthday, he was still working as Chairman of the Board of Customs, and living in London most of the year. His eldest son, also called Thomas Fremantle, was also living in London, where he was a Director of the London, Brighton and South Coast Railways. Another son, Edmund, who was a captain in the navy, but on shore leave and half-pay, was living in Swanbourne at the time.

Meanwhile, a Bucks Labourers Union had been created and in Warwickshire, under the leadership of Joseph Arch, a Methodist local preacher, a National Union had been formed. In no time, branches of the union had been formed in villages around Bucks. Swanbourne’s Union was centred on the Methodist chapel, which had been purchased only a couple of years earlier. Most of the chapel men were agricultural labourers, and supported the union.

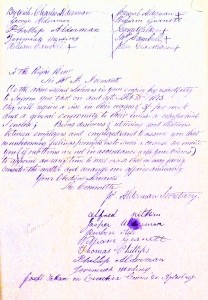

On Saturday 15th February 1873, the union sent letters to Sir Thomas Fremantle, his son Thomas, and to 3 or more of the other tenant farmers in the village with their demand of a 3 shillings a week pay rise, and also ‘conformity with the rules of the union’ or else they would call a strike. Letters went from Swanbourne to London, written by various people including Edmund Fremantle, William Phillips – Sir Thomas’s bailiff and John Phillips who managed Thomas Fremantle’s house, updating them on events in the village. Sir Thomas and his son wrote back with their instructions, the main one of which was to say that they would have nothing to do with the union, but were willing to give a pay rise if the men left the union and promised not to have anything further to do with it.

Although the strike was delayed by a week, to allow time for some discussion, the refusal to deal with the union was unacceptable to the workers, and on Saturday 1st March, around half the men failed to turn up for work – and the strike was on. To start with, the men were confident that Sir Thomas would meet their demands, as they believed that justice was on their side and he was a compassionate man. But he held firm, and would only give a rise to those who had left the union. Some of the men began to look for work elsewhere, and around ten men went to Leamington to meet up with employers from the North of England, whilst their wives started selling furniture to make ends meet. A few others looked at the possibility of emigration, and at least 3 eventually went to Queensland in Australia.

However, the workers had little in the way of financial reserves, and even with support from the Union, money quickly ran out. By the third week, some workers were beginning to return to work, and by Wednesday 19th March, the strike was coming to an end. Sir Thomas travelled down from London on Friday 21st March, to speak with his men. Nearly all seem to have chosen to leave the union, to accept whatever rise was offered, and to safeguard their jobs. The strike was at an end.

Although Joseph Arch himself visited Swanbourne a few weeks later, there was little enthusiasm for further Union activity. As Sir Thomas wrote in his diary, “Mr. Arch’s visit was evidently intended to counter all the injury done to the cause of the Union by the premature strike which took place in the village a short time ago”. Probably lessons were learned on all sides, and a better way of sorting out differences over pay prevailed.

Swanbourne Strike letter, 1873 pdf

CLICK HERE for a new, revised and detailed account of the Agricultural (50 pages long) which is now available as a PDF after being meticulously researched by Ken Harris:- The Swanbourne Agricultural Workers Strike; full updated account as at 16.1.14 by Ken Harris

RETURN to Historical Events Category