Feeding the poor in Swanbourne

A soup kitchen in late nineteenth-century Swanbourne

by Phil Carstairs PhD

For many of the residents of late nineteenth-century Swanbourne, times were hard. The parish was largely a farming community; its three cottage industries, lace-making, straw-plaiting, and boot and shoe making were in terminal decline; the latter which had employed people from eight households in 1851, employed only two families by 1871. Earlier in the century women working in lace or straw plait were often capable of earning more than most farm workers, but foreign competition, mechanization and changes in fashion made both starving work by the last quarter of the century.

For the men working in farming things were no better. In the 1870s, farming in Britain was entering a decade long recession that reduced incomes and depressed wages. The attempts at unionizing the rural workforce and raising rates of pay, in which many of Swanbourne’s labourers had eagerly participated, achieved a pay rise but prospects remained gloomy. Some younger workers emigrated. For those that remained, there might have been less competition for work but this did not improve wages greatly. And, if you could not work, what? Welfare, relief under the Poor Laws, was limited for most to a stay in the Winslow Workhouse, particularly after 1870 when outdoor relief (aid outside the workhouse) was curtailed. In the 1851 census at least a dozen people, mostly elderly, were recorded as being paupers (i.e. receiving outdoor relief), by 1881 there were none (although this might reflect the information collected rather than reality). For much of the nineteenth century, local charity played a significant role in helping people survive hard times, and in rural areas this was provided mostly by local landowners. Swanbourne was no different.

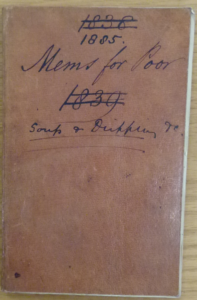

Included in the Fremantle family papers is a small exercise book, the front cover of which was originally headed ‘1838 Mems for the Poor 1839’. The dates have been crossed out and replaced with 1885 and the words ‘Soup & Dripping &c’ added in a different hand (Figure 1). Inside the front cover the inscription reads ‘Memorandums of Soup for Poor Swanbourne Nov 1838’; the date is again crossed out and replaced with ‘1885’. Unfortunately almost all the pages from those early years have been removed except for two entries for the ‘Baby Linen Account’ for 1840. These record the loan of linen to two families with new-born children, Charlotte Collyer daughter of William and Martha Collyer and Mary Pitkin, daughter of Daniel and Mary Pitkin. The families of agricultural labourers could not afford luxuries such as linen.

When the New Poor Law was implemented in Winslow Union and the Workhouse built the Fremantle family probably started providing winter soup to the poorest in the village and assistance to new mothers to reduce the need for them to apply for parish relief (which risked their being sent the workhouse). It is not clear for how long soup or linen was continued after 1840 or why the Fremantle family restarted providing soup in 1885, or indeed saw a need to record it.

The Swanbourne soup kitchen was not run on lines typical of most contemporary English parish soup kitchens. There were usually two or three distribution each week and each day’s entry records soup and dripping being given to between six and ten households. A total of 56 different households were given soup over the six-year period in a total of 207 distributions. The soup recipients were probably selected (the list was never the same two groups in succession) and notified that soup was available. There is no discernible pattern of which days soup was served on although Wednesdays, Thursday, Friday and Saturday were the most common days.

The limited number getting soup each day suggests that only a few gallons (a large pan) of soup were made on each occasion; a quart of beef soup being the standard serving at most soup kitchens nationwide. A typical parish soup kitchen might make 60-100 gallons of soup for a day; it would usually run from late December to the endof March, opening on set days each week and served all its ticket-holders with soup and bread. It may be that the Fremantles delivered the soup and dripping as part of a scheme of parish visiting. A slip of paper within the book divides the October 1890 distributions into Nearton and Smithfield End and the individuals selected each day seem often to follow this pattern. This would make delivery more practical.

There were ‘regulars’: on the soup list: four recipients, Dinah Walker, Mrs Charles Alderman, Mrs Barbara Sheffield and Henry Alderman senior each appear over 100 times on the list (Mrs Walker was so well known to the list-keepers that she was almost always referred to simply as ‘Dinah’). About half of the list appear fewer than 10 times.

We do not know how many people in each household the soup was meant to serve; almost all the households were multi-generational and may have had lodgers too. The named recipients were elderly (their average age was 56 in 1886) and when we look at who attended most, 61 to 80 year olds attended on average 50 times during the six years whereas 21-40 year olds averaged only 14 deliveries. Soup was clearly targeted primarily at those who were too old to support themselves fully. Occasionally if wintertime unemployment was severe, younger names appear on the list; they were either unemployed due to the weather or perhaps ill or injured.

Thirty six of the 56 households on the list were headed by agricultural labourers, farmworkers and one shepherd and 10 were headed by wives or widows of agricultural labourers (several of these worked making lace, sewing, cleaning or doing laundry). The remainder were lace-makers, straw-plaiters, a seamstress, a servant and three widows. Only two people on the list cannot be identified in census records. There was very little work in the village other than farming once straw-plait and lace-making had died out, and this did not pay well enough for people to save, which is reflected in the list of those getting soup.

Data spreadsheet in EXCEL:- Soup kitchens in Swanbourne

Fourteen or 15 individuals on the list of soup recipients had participated in the farmworkers’ strike of 1873. They received soup on an average of 20 occasions; this is less than the average for the whole list of 29 occasions. However, again using people’s age in 1886 as the yardstick, the average age of the former strikers who got soup was 48, less than average age of whole list, 56. People aged 56 or younger appeared on the list an average of 18 times, whereas people over 56 appeared an average of 38 times. There was no discrimination against former strikers still resident in Swanbourne in terms of soup distribution. Age was a more significant factor in determining whether a person got soup than whether they had participated in the strike.

The exercise book, now in the Buckinghamshire Archives, is a rare window into social relations in late nineteenth-century Buckinghamshire, where wealthy landowners continued to provide charity to those who worked their land. The Fremantle’s also encouraged a co-op store and a benefit society in the village but would not tolerate an agricultural worker’s union. Such charity served to maintain the social order. The soup distribution could promote solidarity and help smooth over fractured relations, but to receive charity from your employer and the owner of your home required a degree of deference that some may have found hard to stomach.